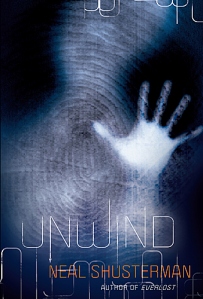

The Feminist Lens: Unwind by Neal Shusterman

In the future of America, after the Heartland War, abortion is made illegal. The Heartland War, after all, was not a war involving any military, but was a war between the pro-choice and pro-life forces in America. The war got so bad that the American military had to be asked to come in as a mediating force to stop the fighting. It was suggested, as a compromise, and also as a bit of sarcasm, that abortion could be made illegal, but once a child turns thirteen, and no later than the child is eighteen, the parents can decide to unwind their children. This means that their children are sent to “harvest camps” and their organs are harvested and given to others. The law states that 100% of the body (actually 99.4%, which accounts for unnecessary organs like the appendix) needs to be used, so people started to buy things like new teeth or hair. The organs that don’t function properly – like one boy’s asthmatic lungs – are sold cheaper than those which function extremely well. This compromise was accepted because everyone was just so sick of fighting.

In the future of America, after the Heartland War, abortion is made illegal. The Heartland War, after all, was not a war involving any military, but was a war between the pro-choice and pro-life forces in America. The war got so bad that the American military had to be asked to come in as a mediating force to stop the fighting. It was suggested, as a compromise, and also as a bit of sarcasm, that abortion could be made illegal, but once a child turns thirteen, and no later than the child is eighteen, the parents can decide to unwind their children. This means that their children are sent to “harvest camps” and their organs are harvested and given to others. The law states that 100% of the body (actually 99.4%, which accounts for unnecessary organs like the appendix) needs to be used, so people started to buy things like new teeth or hair. The organs that don’t function properly – like one boy’s asthmatic lungs – are sold cheaper than those which function extremely well. This compromise was accepted because everyone was just so sick of fighting.

Unwind sets us up in this dystopia following the Heartland War and follows three Unwinds, as the children who are going to be unwound are called, who run away and fight for survival. I won’t give away much of the plot in this one, because I think that it is secondary to the political and religious agendas raised in the book. I was first introduced to this book by one of my students who read it in his literacy support class last year and loved it. When he described it, I was intrigued, thinking it would be all about how pro-choice people have the right idea because “unwinding” a teenager – essentially killing him or her – is sort of ridiculous. But that really wasn’t the political agenda in the book. Yes, the idea of unwinding a teenager is presented as awful, and the parents who choose it are also presented as sufficiently awful to be able to do this to their teenage child. However, there are debates back and forth between the runaway Unwinds and within their inner thoughts about which is better – unwinding or abortion – and we are really left to believe at the end of the book that there is no good option, even though it is set up as understandable that raising a baby can be difficult or even impossible, and raising a troubled teenager can, at times, be the same.

The religious debate, however, was more clear-cut. One of the runaway Unwinds the story follows was a tithe, or a child that was given up to unwinding because religion calls for a donation of 10% of all the family has – money, possessions, and – yes – children. It doesn’t seem that there is a single religion that doesn’t call for this, actually, and the almost over-dramatic, sensational ending (that I won’t give away because as over-dramatic and sensational as it was, you’ll still want to be surprised) leaves us with a foul taste in our mouths about religion in general and what kind of person it can create if taken too far.

Shusterman does a fantastic job of developing this dystopian society and setting up rules that answered pretty much all of the questions I could think of about the laws that had come into place. For example, women who had babies but couldn’t take care of them still had an option called “storking.” They could “stork” a baby, which meant they could leave the baby on the doorstep of a home. If the mother got away undetected, the baby was the legal responsibility of that family. If the mother got caught, she was officially legally responsible for the baby herself. After that, the option would be a state home, where children could live until thirteen and then be unwound most likely. Shusterman obviously spent a lot of time thinking through his society and the rules, which I think is an absolute must for a successful dystopian society (*ahem* The Hunger Games, anyone?). However, I was less than enamored with the format of the book. Each chapter jumped to the perspective of a different character, although the entire book was written in the third person. So, as readers, we were shuffled between one third person limited point of view to another, and because of this, I felt as if I couldn’t build up an attachment to any of the characters because, as soon as I did, I was ripped away to yet another character. If it was limited to just the three characters, I think I would have been less disappointed with the format of the book, but toward the end, there were all sorts of characters – even some that would be considered flat characters, and I think that did little to push the story forward or add to the suspense of the novel.

Although I was left wishing I knew what the “agenda” of the book really was as far as abortion, I was pleased by the fact that, as a YA novel, the point of this book was to stimulate discussion, not to preach. As much as I may have my own agenda about certain issues, I’d much rather have my students come up with their own, informed opinions rather than push my agenda on them – which is perhaps what Shusterman was trying to tell us regarding the religion part of the book. The more agendas – both political and religious – are pushed on children and teenagers, the more teenagers are apt to rebel against those agendas. In that way, then, I’m glad Shusterman didn’t push an agenda about abortion, and I think it’s pretty clear at the end that, at least, the idea of unwinding a teenager is completely unfair and that a different alternative needed to be presented. It is also empowering for teenagers because they are shown that, with protests and petitions, they can make a very real change in society. And, although the ending is a bit over the top, that point still does ring very true.

This is book 1 of 50 in my 30 Before 30 goal #15.